Friendly giants in the schoolyard

When I was a child, growing up in the ranch country of northern Nebraska, we lived in a low-lying valley with two creeks and big sandy hills all around us. I attended a little one-room country school, about two miles from my house.

I can't imagine my childhood in that school without the big cottonwoods (Populus deltoides) that grew on the schoolyard. The trees were very much a part of our playground experience. Most importantly, without the cottonwood trees, we'd have had no place to hide when we played "Hide and Seek."

I can't imagine my childhood in that school without the big cottonwoods (Populus deltoides) that grew on the schoolyard. The trees were very much a part of our playground experience. Most importantly, without the cottonwood trees, we'd have had no place to hide when we played "Hide and Seek."I remember affectionately one very large cottonwood that grew in the ditch just off the school property. In truth, we weren't supposed to venture off the grounds, but the teacher never said anything about us hiding behind that tree. Its trunk was so large that several of us could hide there together -- that's why we liked it so much.

Behind the barn (a relic of the time that children rode horses to school), the big boys had nailed some boards to two cottonwoods that grew close together. If you were brave and naughty (as the big boys were,) you could climb those boards like a ladder, get on the barn roof, and slide down on the other side.

In the fall, we played in the leaves, and in the spring, we enjoyed the beaded strings of "cotton" and the red blossoms. And of course, we all knew how to fold a cottonwood leaf and make a whistle.

I remember how outraged we all were when the school board (our fathers!) cut down one of the big old trees one day. They said it was threatening to fall on the schoolhouse.

I don't know if the trees sprang up from seed originally, or if they had been planted. They were mature trees in the 1950s and 1960s when I was a child.

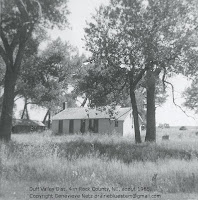

In 2000, when I visited the little, vacant schoolhouse, many of the big trees were dead, standing like whitened skeletons around the playground. Cottonwoods live about a century, and their time was complete.

"The power to recognize trees at a glance without examining their leaves or flowers or fruit as they are seen, for example, from the car-window during a railroad journey, can only be acquired by studying them as they grow under all possible conditions over wide areas of territory. Such an attainment may not have much practical value, but once acquired it gives to the possessor a good deal of pleasure which is denied to less fortunate travelers."

"The power to recognize trees at a glance without examining their leaves or flowers or fruit as they are seen, for example, from the car-window during a railroad journey, can only be acquired by studying them as they grow under all possible conditions over wide areas of territory. Such an attainment may not have much practical value, but once acquired it gives to the possessor a good deal of pleasure which is denied to less fortunate travelers."